-

A warning from Jamelle Bouie in The New York Times

Saturday October 19, 2024Let’s hope someone has a Plan B if this shit goes down — from @jbouie of the NYT:

There is no reason to act as if the former president is issuing idle threats, especially given his efforts as president to wield violence against protesters, migrants and other perceived enemies of the state. “When he was president,” Asawin Suebsaeng and Tim Dickinson report in Rolling Stone, “several ideas that Trump repeatedly bellowed about in the Oval Office included conducting mass executions, and having U.S. police units kill scores of suspected drug dealers and criminals in urban areas in gunfights, with the cops then piling those corpses up on the street to send a grim message to gangs.”

The only reason these fantasies never became reality is that his aides and top officials either ignored or refused to carry out his orders. Next time, he’ll be surrounded by loyalists and sycophants. Next time, we won’t be so lucky.

There Is No Precedent for Something Like This in American History

-

The lying classes are winning against fact-checking

Friday October 4, 2024Fact-checking was a promising solution for addressing the explosion of misinformation and disinformation online. But it has been proven ineffective at combating the sheer amount of bullshit that inundates people wherever they get their information. Now it seems that the politicization of fact-checking is having a major deterrence on these efforts, with the lying classes winning the battle.

We need new solutions to combat untruths online, which is only getting worse with AI junk.

-

Writing with Generative AI

Thursday October 3, 2024I’ve been exploring how to use Generative AI tools in my writing practice, so I was excited to see this story in The New Yorker that reflects back some of the experiences I’ve had with them. Here’s an interesting excerpt:

The chatbot couldn’t produce large sections of usable text, but it could explore ideas, sharpen existing prose, or provide rough text for the student to polish. It allowed writers to play with their own words and ideas. In some cases, these interactions with ChatGPT seem almost parasocial.

-

Friday August 2, 2024

Apple really needs to up the game! Why just foldable? That’s so Samsung. How about rollable? Come on. iPhone Fold to be joined by foldable iPad

-

Friday August 2, 2024

Did anyone else read this article published by The New Yorker about Spotify? I only got on the platform last year, so I don’t know how shitty it has become. Why I Finally Quit Spotify 🎵

-

Friday August 2, 2024

Tremendous work of literature! I can’t recommend it enough. It is devastating and complicated, both a dialogue with Mark Twain and a response. James by Percival Everett 📚

-

music

Thursday August 1, 2024Very much enjoying the Drowned in Sound newsletter and its take on music & algorithms, channeling the frustrations with how music is found (and not found) with the rise of bots:

With those pesky gatekeepers like music critics and radio hosts slain¹, we now must make offerings to our robot overlords. Forget blood rituals, they want your soul, sweat and tears (and cash), to decide whether they agree that what you have created resonates with their data-points.

🎶

-

Latino/a

Wednesday July 31, 2024Sixty days until Claudia Scheinbaum is inaugurated as Mexico’s first female president. Here’s an interesting analysis of her rise to power along with the “hegemonic” Morena party. www.csis.org/analysis/…

-

Rebuilding Local News in the UK

Wednesday July 31, 2024Interesting story about efforts to rebuild local news in the UK. I like the subscription-first model because it harkens back to the strength of the newspaper business. My question is always whether there is a local audience for this type of coverage. www.theguardian.com/media/art…

-

Sunday June 30, 2024

I wrote about the last album by the Mexican band Caifanes for Grammy.com - Revisiting “El Nervio del Volcán” 🎵

-

Wednesday June 26, 2024

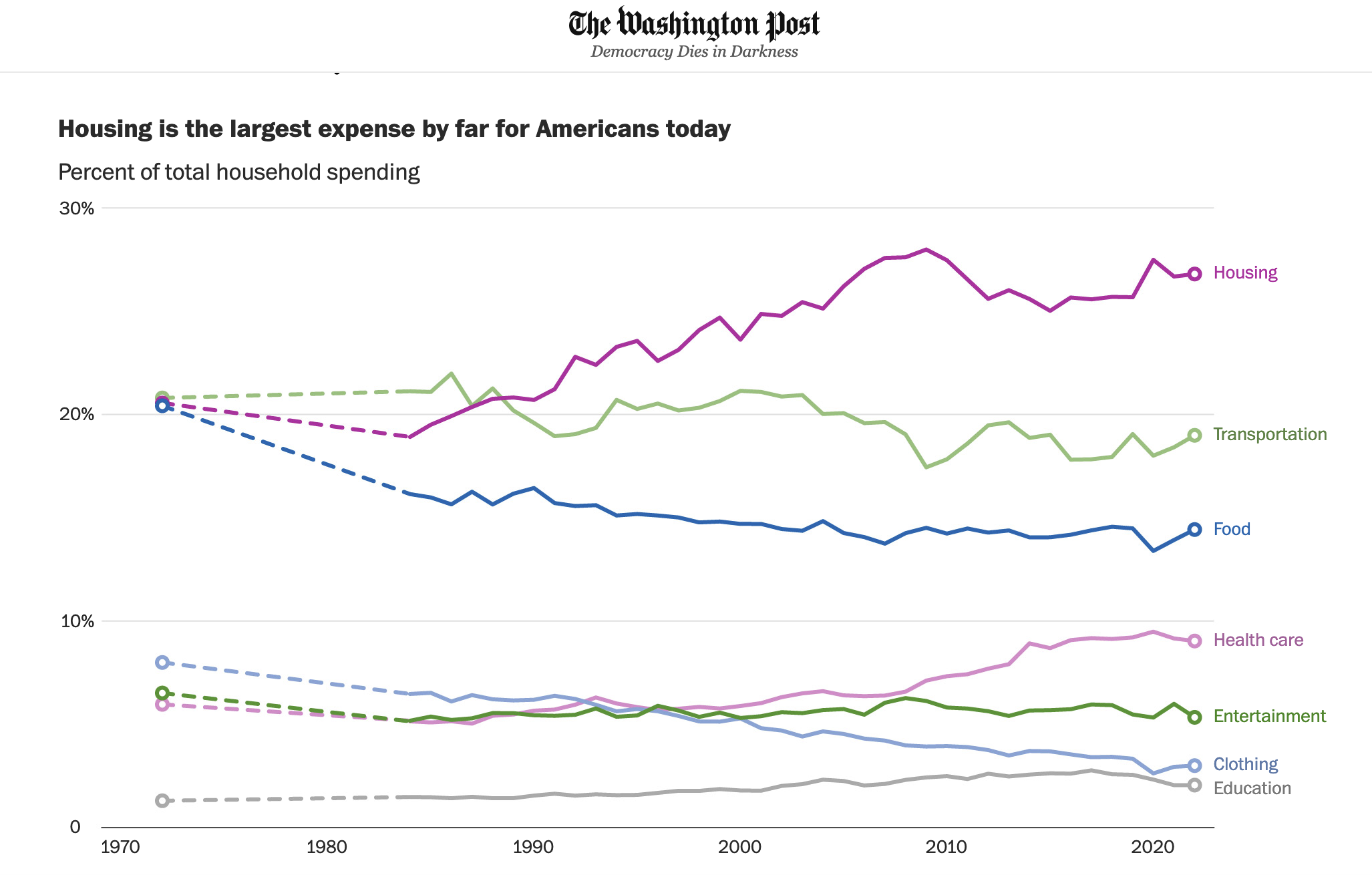

The Washington Post shows why so many Americans are feeling an economic crunch: Housing costs are out of control.

-

Tuesday June 11, 2024

I do not want an AI iPhone. Apple Intellgence sounds like a privacy nightmare. There’s no guarantee that they will do no evil with the data being sent to their services. OpenAI is a malicious company. More from Disconnect

-

Monday June 3, 2024

What would a federated news organization look like? What would the benefits be?

-

music

Thursday May 30, 2024🎵 Didn’t like Mengers when I first heard them (maybe I wasn’t in the mood at the time), but now I’m addicted to their album “Golly”:

-

Wednesday May 29, 2024

I read that the fediverse will save us from Big Tech. But for godsakes, how many tutorials do I have to read to understand it? What the hell? I am also wary of anything that the Instagram head honcho has embraced.

-

Sunday May 26, 2024

Great conversation on 🎙️Search Engine: Are news orgs ready for what is expected to be a web traffic catastrophe?

-

music

Que vergüenza: Only one Spanish-language album makes it on Apple Music list 🎶🎵

Thursday May 23, 2024Congrats to Bad Bunny on having the only Spanish-language album on Apple Music’s List of 100 Best Albums. I agree that “Un Verano Sin Ti” is a masterwork. But I can name a few other Spanish albums that are just as deserving: “Motomami” by Rosalía, “Re” by Café Tacuba, and maybe even “Matamoros Querido” by Rigo Tovar.

-

Ha Ha

Red Lobster Goes Broke Over Shrimp. Or Did It?

Tuesday May 21, 2024The endless shrimp did in Red Lobster! A lesson in the consequences of overconsumption and capitalism? It’s fishy, for sure. One Bloomberg writer imagines the CEO at a meeting discussing a conspiracy to flood the market with cheap crustaceans:

Then he gets up from the table and shrimp fall out of his pockets and he walks out of the boardroom trailing shrimp everywhere, this is what corporate finance is all about.

-

Latino/a

Tuesday May 21, 2024Delicious! First taco stand ever to receive a Michelin star is based in Mexico City. The chef says their secret is “simplicity.” The Associated Press

-

music

Saturday May 18, 2024Despite illness, Echo & The Bunnymen put on a fantastic show in DC 🎵

-

music

Thursday May 16, 2024Portuguese industrial anyone? Maquina 🎶🎵

-

Wednesday May 15, 2024

There are so many good lines in this Platformer story, but this one makes it clear how Google is on the verge of fully capturing the web through AI. Google’s broken link to the web

Over the past two and a half decades, Google extended itself into so many different parts of the web that it became synonymous with it. And now that LLMs promise to let users understand all that the web contains in real time, Google at last has what it needs to finish the job: replacing the web, in so many of the ways that matter, with itself.

-

art

Wednesday May 15, 2024I took a collage workshop. Here is what happened. Any other collage fans out there? 🎨

-

art

Wednesday May 15, 2024A highlight for me at the Independent fair in NYC: Sculptures by Anna Tsouhlarakis

-

tech

Friday May 10, 2024